Prologue

‘Great for the City’: The Rise and Fall of Bobby Valentine and the New York Mets, 1962–1998

I JUST ENDED MR. BASEBALL’S CAREER.

The boy was roughhousing and it was all fun and games until he landed a shot to his friend’s eye. The boy’s heart sank because his friend wasn’t just any teenager. His friend was Mr. Baseball, aka Bobby Valentine. This was the 1960s, in Stamford, Connecticut, a time and place in which Bobby Valentine was everything.

As a high school athlete, Bobby Valentine dominated all sports. His skill as a running back garnered comparisons to O. J. Simpson from Simpson’s own coach at USC. He was so good at basketball that for years local coaches could chide a showboating youngster by yelling, “Who do you think you are, Bobby Valentine?” He excelled at more esoteric endeavors too, winning pancake-eating contests and ballroom dancing competitions with equal gusto. If an event ended with crowning a winner, Bobby Valentine would find some way to be that winner.

Above all, Bobby Valentine preferred to win at baseball, his one true love. The lights outside his house were covered in baseball-shaped globes, lovingly painted by a carpenter father who shared Stamford’s belief that Bobby Valentine could do no wrong. He was son to them all, a local treasure to be cherished and protected. That’s why, when a boy landed an accidental elbow to Bobby Valentine’s eye, that boy feared that he might have destroyed the hope of an entire city.

Bobby Valentine shrugged off this blow. Nothing could stop Bobby Valentine. If your entire hometown called you Mr. Baseball before you reached adulthood, you would believe you were bulletproof, too. The problems would only come when you left that town and entered a world that didn’t see you glowing with the same angelic light. That world might never make any sense to you at all. You might never make any sense to that world.

Bobby Valentine was the Los Angeles Dodgers’ first-round draft choice in 1968. His athletic range was matched only by his relentless enthusiasm and his inability to repress a high-octane personality. His rookie league manager—a baseball lifer named Tommy Lasorda, who would become a mentor and lifelong defender—described him as “insufferable, but in a good way.” Valentine hit his way through the Dodger organization with breakneck speed, inspiring the big league club to call him up during the 1969 season.

Then Valentine was forced to slow down for the first time in his life by Walter Alston, human speed bump. Alston had managed the Dodgers since they called Flatbush home and had no patience for Valentine’s impatience. Each year, Alston accepted a one-year contract offered by the Dodgers’ parsimonious owner, Walter O’Malley, and he expected his charges to display comparable humility. Alston used Valentine all over the field, treating him more like a utility player than a budding star. Mr. Baseball responded by openly lobbying for Tommy Lasorda to take Alston’s place, then gave the current manager more ammo to use against him when he injured his knee in an intramural football game before the 1972 season. A mediocre season at the plate and continued clashes with Alston prompted a trade to the Angels at year’s end.

On May 17, 1973, while patrolling center field at Anaheim Stadium, Valentine pursued a long fly—at full speed, of course. As the ball sailed over the fence, he crashed into its unyielding expanse of chain link. Valentine caught a cleat in the fence and snapped his right leg in two places, so horrifically that bone poked through the skin. The break was then set improperly, causing his right leg to heal slightly shorter than the left. The legs that had once powered Valentine to break state rushing records now tripped underneath him as he ran out grounders.

Finished as an everyday player, Valentine settled into life as a benchwarmer with the Angels and Padres before being dealt to the Mets midway through the 1977 season. He performed well enough the following year to receive assurances from his manager that he would make the opening day roster in 1979. Then, with only a week left in spring training, the team released him, citing the need to give chances to younger players with more potential. The manager who delivered the bad news did his best to be civil, but it was obvious that Valentine’s career was all but over. Once assured a roster spot and steady paycheck, all Valentine had left was a shrug of the shoulders and best wishes from his now-former manager, Joe Torre.

Valentine muddled through sixty-two more major league games before hanging up his spikes at the ripe old age of twenty-nine. Then he returned to Stamford to open a sports bar that bore his name. Though the town had filled with new pieds-à-terre for the Wall Street crowd, Valentine opened his bar south of I-95, where the town retained some of the working-class character it held in his youth, where the memories were longer and he was still greeted as Mr. Baseball.

On the walls of his bar, Valentine hung his prized collection of baseball memorabilia alongside a morbid memento: pictures of that fateful night in Anaheim, strobed one frame at a time. You see him approaching the wall, getting closer with each blink. You can tell he won’t be able to stop himself. His momentum is too great. A terrible finish is in store. And then you see it. You see Mr. Baseball sprawled out on the turf in agony, his leg shattered, his old life already over.

After one year as a saloonkeeper, Bobby Valentine accepted a minor league instructional assignment with the Mets in 1981. Once again, he worked his way to the bigs at fevered pace. By 1983, he was on the Mets’ big league coaching staff. By 1985, he was tapped to manage the Texas Rangers. Under Valentine’s stewardship, the moribund franchise experienced a rare brush with contention, finishing second in the American League West in 1986, its best showing ever. But no matter where the Rangers were in the standings in any given season, the spotlight would always focus on their excitable manager.

Bobby Valentine refused to keep still in the dugout, shifting from one bad leg to the other, pacing, shaking his head, throwing up his hands. He would often position himself on the dugout railing to berate all of his presumed enemies, earning him the nickname Top Step and the ire of opposing managers. He was more popular with his own team, but not by much. Kevin Brown, the Rangers’ ace, grumbled that when Valentine’s players went through slumps, the manager shut them out, as if their bad luck would infect the rest of the team. The local press could sympathize with Brown’s feelings. Simple queries from the beat writers provoked answers that ranged in tone from dismissive to combative, delivered in a voice that came from the back of the throat, guttural, mocking.

Such sins could have been excused if Valentine’s teams succeeded, but the runner-up finish in 1986 proved his high-water mark in Texas. He received his pink slip in July 1992, the bad news delivered at a dour press conference led by Rangers team president George W. Bush.

Valentine managed the Mets’ triple-A affiliate for one season before the 1995 season brought him an offer to become the first manager recruited directly from America to lead a team in the Japanese major leagues (Nippon Professional Baseball, or NPB). The offer came from the Chiba Lotte Marines, a down-on-its-luck franchise willing to try anything to win, or at least gain some attention. Despite the glaring cultural differences and the Marines’ lowly status, Valentine jumped at the challenge.

That challenge came at a crucial time for Japanese baseball, for 1995 was also the year of Hideo Nomo’s historic “rookie” campaign. The star pitcher for the Kinetsu Buffaloes “retired” from NPB so he could sign with the Dodgers, making him the first Japanese player to make a jump to the American major leagues in almost thirty years. Nomo’s immediate stateside success made him a source of great pride to a baseball-obsessed nation, and the ensuing Nomo-mania inspired American teams to send scouts overseas in the hopes of finding the next Japanese superstar. Though Valentine was new to Japanese baseball himself, he became the go-to quote for Americans hoping to make sense of it all.

See for example Valentine opining to the New York Times on the quality of Japanese pitchers in July of 1995, at which point he’d been on the job in Japan for only a few months. See also an interview conducted after Valentine’s abbreviated time in Japan, in which he proclaimed Ichiro Suzuki could make the transition to MLB—not a bold prediction for anyone who’d seen Ichiro play, but very few Americans, even major league scouts, had seen Ichiro at that point.

Such hubris grated on Valentine’s bosses, and before long, team officials were undermining their new manager at every turn. First, the Marines fired the interpreter and head coach who had tutored him on NPB’s players, with no explanation, and instructed Valentine to read up on “the book” of NPB players and their stats instead. When reminded that said book was only available in Japanese, a language Valentine could not yet speak or read fluently, Valentine was told to study harder. After receiving verbal promises for a three-year contract, he was offered a paper contract for two years.

Despite these considerable hurdles, Valentine piloted the Marines to a second-place finish and their best record in eleven years, which only infuriated his bosses further. At season’s end, the Marines’ front office publicly called out Valentine for his training methods. (Japanese teams traditionally relied on rigorous individual drills, whereas Valentine preferred team practices.) The Marines’ general manager contended they finished second in spite of Valentine, not because of him, while an assistant general manager said Valentine “was judged deficient in baseball ability.” Fans gathered twenty-four thousand signatures on a petition demanding Valentine’s return. He was fired regardless.

The Mets welcomed Valentine back to manage their triple-A team again in 1996. In spite of the Marines’ best efforts, his misadventure in Japan hadn’t humbled him in the least. As far as he could see, he was still Mr. Baseball. It was only a matter of time before the Mets would see it that way too.

When Valentine returned to the Mets, the franchise was in the midst of one of its periodic ruts while the Yankees were on the rise. In isolation, this state of affairs was not unusual, as the two teams’ fortunes had traditionally moved in complementary waves. In the mid-1960s, the Mets were regarded as more in touch with the dynamic go-go New Frontier feeling of the era than the Eisenhower-gray Yankees. The Mets’ brand-new home, Shea Stadium—convenient to several new highways and the Long Island suburbs to which so many New Yorkers had fled—was far preferred over the Yankees’ outdated home in the South Bronx, ground zero for Robert Moses–induced white flight. The contrast only grew sharper when the Mets won a shocking championship in 1969, then scrambled from last place to first in the final months of the 1973 season and came within one game of another World Series trophy. Beginning in 1964 (the year Shea Stadium opened), the Mets outdrew the Yankees for eleven straight seasons, and the tallies were seldom close.

The contrast was made even starker beginning in 1974, when renovations at The House That Ruth Built forced the Yankees to play home games at Shea Stadium for two full seasons. A day before their “home opener” in 1974, the Yankees betrayed their discomfort over being forced to play in Queens—and perhaps conducted a silent protest against this indignity—by warming up on a chilly infield while wearing road grays instead of their usual pinstripes. The opening day starter for the Yankees, Mel Stottlemyre, told the TV crews on hand to capture the sad spectacle that he felt like he’d been traded.

The tide began turning in 1975 with the death of baseball’s reserve clause, which opened the door to free agency. The resulting explosion of player salaries was too much for the Mets’ owners, the de Roulet family, so parsimonious they once considered collecting foul balls and scrubbing them for reuse. At the 1977 trade deadline, team president M. Donald Grant shipped the team’s two brightest stars, ace Tom Seaver and slugger Dave Kingman, out of Queens in a shortsighted effort to keep down payroll. These moves came to be known as the Midnight Massacre, for to Mets fans they were about as shocking as their namesake Watergate firings, and would doom the team to irrelevance for years to come.

Meanwhile, the Yankees took up residence in a renovated Yankee Stadium in 1976, while their new owner, George Steinbrenner, embraced free agency as much as the Mets ran from it and inked stars like Reggie Jackon and Catfish Hunter to large contracts. The resulting clubhouse mix was a volatile one dubbed The Bronx Zoo, but these Yankees nonetheless won two consecutive championships in 1977 and 1978 and drew crowds that abandoned the hopeless Mets. Once-packed Shea Stadium became known to embittered fans as Grant’s Tomb.

The next reversal of fortune began in 1980, when the Mets were sold to a group headed by publishing heir Nelson Doubleday, who then hired Frank Cashen as his general manager. Architect of the great Orioles teams of the 1960s and 1970s, Cashen rebuilt a decimated farm system and concocted savvy trades to fulfill his promise to make the Mets contenders again in five years’ time. By 1986, another championship was theirs. By 1988, over three million fans were showing up at Shea each season. As for the Yankees, they lapsed into mediocrity and could find little traction with a sports press fixated on the more exciting and successful Mets, unless it was news about George Steinbrenner’s ineffectual and embarrassing meddling.

The 1986 championship looked like the first leg of a Mets dynasty, but that magical season proved to be the era’s crest. The Mets’ decline proceeded slowly at first, one small slip at a time. Another run at the crown in 1988 was snuffed by a seemingly inferior Los Angeles Dodgers team, which beat the Mets in a seven-game championship series behind a magical year from pitcher Orel Hershiser. Staff ace Doc Gooden struggled with substance abuse and drew multiple suspensions for violating the league’s drug policy. Darryl Strawberry feuded with management and left for Los Angeles. Frank Cashen traded away valuable budding stars like Kevin Mitchell, Lenny Dykstra, and Randy Myers and watched all of them power other teams into the playoffs. Manager Davey Johnson continually clashed with the front office until he was canned in 1990. Johnson’s replacement, Buddy Harrelson, made it clear he was not made of managerial timber when he withered under criticism and literally hid from the press. Before long, he too was gone.

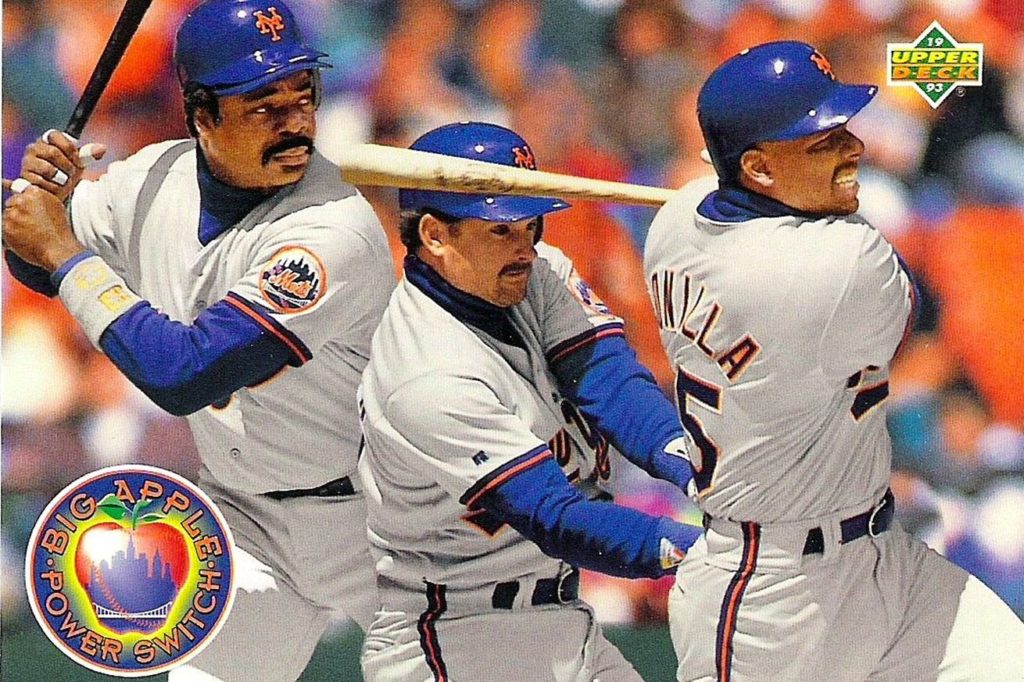

Then assistant general manager Joe McIlvaine, Cashen’s heir apparent, blindsided the team by leaving for the San Diego front office after the 1990 season. Another assistant GM, Al Harazin, ascended to second in command by default when Frank Cashen retired after the 1991 season. Harazin had previously dealt exclusively with the money side of the business and was judged “dangerously shallow” in baseball knowledge by co-owner Fred Wilpon. What Harazin lacked in baseball acumen he hoped to make up for with spending power. Both as Cashen’s lieutenant and as GM himself, he successfully lobbied the team to sign pricey stars like Vince Coleman, Eddie Murray, Bobby Bonilla, and Bret Saberhagen. These acquisitions made the Mets a chic pick to return to their former glory, but the 1992 season (Harazin’s first at the helm) was doomed by injuries, underperforming, and strife on and off the field. Of the latter, the most heinous incidents were rape charges against three Mets players and bizarre rumors that pitcher David Cone had lured women into the Shea Stadium bullpen with promises of autographed baseballs in order to masturbate in front of them. Charges were dropped in the rape case, and a lawsuit against Cone went nowhere (he vigorously denied the accusations), but the cases tarnished the sullen Mets’ reputation even further.

Even so, many observers were willing to give the Mets a mulligan due to the spate of injuries they suffered in 1992 and assumed a healthy team would perform well the next year. As it turned out, the Mets did not endure nearly as much time on the DL in 1993. What they did endure was far, far worse.

From mid-April until the end of June, the 1993 Mets failed to put together a winning streak of any length. Over this stretch, what the team did on the baseball field resembled baseball only in the strictly academic sense. Manager Jeff Torborg received his walking papers by May and was replaced by Dallas Green, whose previous managerial work with the Phillies and Yankees labeled him as a drill sergeant type who could whip the Mets back into shape. Soon, Al Harazin was gone as well, replaced by Joe McIlvaine, who’d resigned his own post in San Diego. It was already far too late for Green’s tough love to have any effect in the dugout, or for McIlvaine’s front office skills to cure a poisoned clubhouse. The moves were little more than deck chair rearrangement on the Titanic. Even worse, the ugliness of the Mets on the diamond was only exceeded by their ugliness off it.

Said ugliness began a mere four games into the season, when outfielder Bobby Bonilla confronted Daily News beat writer Bob Klapisch, who had coauthored a book about the mess of 1992 with the provocative title The Worst Team Money Could Buy. After calling the author a homophobic slur, Bonilla promised Klapisch, “I’ll show you the Bronx,” then smacked away a microphone belonging to a camera crew capturing the whole thing on tape.

On July 7, with the media in the clubhouse for postgame coverage, one Met tossed a lit firecracker behind a group of reporters. No injuries resulted, but skittish reporters demanded to know who was responsible. The offending pyromaniac kept his identity hidden for three weeks until pitcher Bret Saberhagen defiantly confessed to the act. “It was a practical joke,” he sneered. “I wanted to get people’s attention. There are always tons of reporters here when something bad is happening. I don’t like a lot of them.” Asked if he’d been disciplined by the team, Saberhagen all but laughed in his questioner’s face. “What are they going to do, fine me?”

A few weeks later, Saberhagen executed an encore by spraying reporters with bleach from a squirt gun. When caught this time, the pitcher was more contrite, telling the press he’d doused them with bleach “accidentally” and professed no intention of hurting anyone. The shift in tone was due to another horrible incident that had happened in the interim, one that turned the Mets’ season from an ugly farce to a detestable one.

On July 24, after a game at Dodger Stadium, Vince Coleman tossed a lit explosive from the window of a car in the general direction of a group of fans in the stadium parking lot. This was no mere Saberhagen firecracker. The Los Angeles District Attorney’s office later compared it to “a quarter-stick of dynamite.” The ensuing blast injured three people, including a two-year-old girl who suffered corneal lacerations. No one but the victims and the LAPD took the attack seriously at first. Coleman shooed reporters away from his locker the next day with a profanity-filled rant. The Mets waited seventy-two hours before issuing an official response, in which they labeled Coleman’s acts as “regrettable and reprehensible” but also made sure to classify them, with an implied shrug of the shoulders, as “off-field activities.” Dallas Green, reputed bad cop, inserted Coleman into his lineup for three straight games following the incident before public outcry forced a benching. Once he faced felony charges carrying a prison sentence of up to three years, however, Coleman called a press conference to beg forgiveness, his wife and kids in tow for maximum effect. (His eventual punishment would be a one-year suspended sentence plus a civil suit settled for an undisclosed amount.)

These baby steps toward good citizenship proved insufficient for one growing and vocal member of team ownership. New York real estate mogul Fred Wilpon had been a tiny portion of the partnership that purchased the Mets in 1980. Over the following decade, he angled his way into 50/50 control of the team with Nelson Doubleday. Like Doubleday, who was virtually invisible compared to his counterpart in the Bronx, he maintained a low public profile for most of that time, but the Coleman incident changed all that. On August 24, Wilpon called his first-ever team meeting and chewed out his employees for embarrassing the Mets and their city. “You should feel privileged to be able to play baseball in New York,” he told them. “If you don’t feel that way and you want out, let us know. We’ll get you the hell out of here.”

Wilpon then scheduled a press conference to inform the gathered media that Coleman would never play for the Mets again. That the outfielder was owed $3 million the next year and that Wilpon neglected to clear this edict with his front office were deemed unimportant details. “I reached a point where I had to say enough is enough,” Wilpon said.

The Mets had picked a terrible time to be terrible. While they had quite literally made themselves a tabloid punch line—comparing them to another walking embarrassment of the era, Tom Verducci of Sports Illustrated declared the Mets “baseball’s Buttafuocos”—the Yankees had begun their slow climb back to the top, thanks in large part to the most humiliating Steinbrenner blowup of all.

In 1990, news broke that George Steinbrenner had paid a mob-connected FBI informant to dig up dirt on Yankee slugger Dave Winfield and his personal charity. Following an investigation by the commissioner’s office, the owner received a “lifetime ban” from the game. Steinbrenner’s meddling had become so reviled that when breaking news of his ban was broadcast over the Yankee Stadium PA system during a game, the fans in attendance responded with a standing ovation. The Boss’s enforced absence allowed the Yankee front office one brief, blessed respite in which to retain talent in the team’s farm system rather than trading it away for overpriced veterans, and to supplement emerging prospects with judicious free agent signings—two things Steinbrenner’s incessant interference never allowed.

In this manner did the Yankees began to win again, and to reclaim the ground ceded by the awful Mets. In 1993, the Yankees passed the Mets in attendance for the first time since the early 1980s. They would not relinquish that crown for the rest of the decade.

In 1990, almost three times as many New Yorkers professed to be Mets fans than Yankees fans, according to a New York Times/WCBS-TV poll, and many respondents named George Steinbrenner as the reason for their preference. “I always enjoyed the Yankees, but George turned me off,” said one fan who saw the Mets as “a quieter, more classy team.” The team from Queens was not exactly renowned for being quiet or classy during their 1980s heyday—they were, in fact, widely reviled outside New York as the playground bullies of the league—but they were paragons of class compared to George Steinbrenner.

Then Steinbrenner’s team began to win, and perceptions began to change. In 1993, another New York Times/CBS poll showed the Yankees held the edge, claiming 6 percent more fans than the Mets. This gap widened each year that followed as the Yankees first won a thrilling World Series in 1996, then loaded up on even more free agents, created a juggernaut, and decimated all competition in a season for the ages in 1998. By that point, there was no question as to which was the top team in town. The only debate concerned how far the Yankees towered above the competition, or if the Mets offered them any competition at all.

That one team was up and the other was down was nothing new. What had truly changed was the city itself. In 1993, while the Mets were imploding and the Yankees were reviving, Rudy Giuliani was elected mayor. In the years that followed, New York went through a radical transformation that placed the two teams’ respective places in the city’s affections into a brand new context that threatened to solidify those positions into bitter permanence.

Like many New Yorkers of his generation, Giuliani cited the city’s ugly descent into rampant crime and near bankruptcy as the reason for his conversion from JFK Democrat to a law-and-order Republican. Appointed as US attorney in 1981, he rose to fame by prosecuting mobsters and Wall Street insider traders with equal levels of pit bull tenacity. The president who appointed Giuliani, Ronald Reagan, would be his explicit political model. He never had The Gipper’s way with a crowd or an anecdote, but Giuliani believed deeply in Reagan’s uncomplicated with-us-or-against-us view of the world and understood the appeal this view had to the electorate. Americans turned to Reagan because his good guys/bad guys delineations removed complication from a complicated age. Giuliani believed this view could work even in ultra-liberal New York.

When Giuliani first campaigned for the mayorship in 1989, he rested his hopes on a pledge to restore “quality of life.” The political novice lost a hotly contested race against David Dinkins, an African American Democrat who hoped to be a balm for the city’s simmering racial tensions. Four years under Dinkins brought little relief to crime and even more racial unrest, however, and when the incumbent mayor and the prosecutor locked horns again in 1993, Giuliani squeaked out a narrow victory.

Rudy Giuliani embraced the “broken windows” theory of policing, which urged an aggressive pursuit of small violations under the premise this rendered the commission of all crimes more difficult. His initial targets were hardly master criminals: squeegee men, subway graffiti artists, cars that didn’t move for street cleaning, an overloaded social welfare system. In the grand scheme of things, the laws being broken in all these instances were minor. That was exactly the reason why he chose to prosecute them. Let no one think they can get away with anything in this town anymore, was Giuliani’s unspoken edict.

Not everyone was pleased with the new zero-tolerance New York. Many of Giuliani’s critics declared the “broken windows” methods employed by the NYPD—stop-and-frisk, ticketing, instructions to move along under threat of arrest—were used primarily to harass minorities for the “crime” of walking city streets. The city’s African American community felt strong-arm police tactics were employed harshest of all in their neighborhoods, that his slashing of the city’s welfare system was aimed squarely at them, and that he considered their mere existence in New York to be a criminal act. But there were also many who applauded Giuliani because his administration ushered in the most precipitous drop in crime in the city’s history, an accomplishment that, to them, rendered all other considerations moot. The latter group supported Mayor Giuliani when he defended the NYPD in every alleged instance of brutality, and they agreed when he defined freedom as “the willingness of every single human being to cede to lawful authority a great deal of discretion about what you do and how you do it.”

Whatever one’s feelings about his tactics, it was undeniable that under Giuliani’s watch the numbers of serious crimes—especially murder—fell off a cliff. Giuliani had indeed transformed a city considered unmanageable since its economy cratered in the mid-1970s, with a speed that was stunning to behold. In short, Rudy Giuliani’s way worked. The new mayor and his supporters considered quibbles about the harshness of his methods to be pointless, if not dangerous.

After decades of danger had repelled visitors, tourists began to flock to New York in droves. Developers gobbled up newly valuable real estate, nowhere more dramatically than Times Square, a once seedy outpost of peep shows and porno theaters reborn as a family-friendly center for tourist attractions and corporate headquarters. Manhattan neighborhoods ravaged by drugs and crime in the 1980s became high-rent districts almost overnight. Even outer-borough living became fashionable. Two years into the Giuliani administration, the Times touted Brooklyn’s Williamsburg as “a new Bohemia” where a two-family home now cost the princely sum of $175,000.

To the world beyond New York, Rudy Giuliani was seen as the man who brought America’s largest city back from its darkest hour. And when America saw Giuliani outside of City Hall, the place they most often saw him was Yankee Stadium, watching his beloved Bronx Bombers lay waste to yet another inferior opponent, wearing his lucky team jacket, celebrating as if he too had won.

In the two-team era, whenever New York boasted a baseball champion, that champion uncannily reflected the city’s self-image. The Miracle Mets of 1969 provided a stirring underdog story for a city beginning to unravel. The Bronx Zoo Yankees were a mirror image of a city that in the late 1970s was, quite literally, on fire. The 1986 Mets were also like their era in New York’s history: cocky, drug fueled, dangerous, and doomed to end in tears.

The championship team of the new New York was the 1998 Yankees. Including a run through the postseason that played out as a mere formality, this behemoth won an astounding one hundred and twenty-five games and experienced no hint of adversity along the way. The entire roster was loaded, right down to a bench that sported expensive part-timers poached from poorer teams. For some outside the city, it seemed unfair that the Yankees could afford to stack an entire roster with superstars, that they could pay their sluggers more than the entire payroll of the some of the league’s poorest teams. Inside the city, though, such questions of fairness were considered quaint, if considered at all. The 1998 Yankees were exactly what New York felt it deserved as it barreled toward the twenty-first century. No more struggles. No more lovable losers. Winning and winners only.

New York and its Yankees had risen from the ashes. To question how either had done so was to question excellence itself. It implied you believed things were better the way they used to be, that you might even want to return to those awful days. To root for the Mets now carried a similar implication that you might pine for the violent, coke-dusted New York that tolerated drug abuse and sexual assault and firecrackers and bleach squirtings; the New York that Rudy Giuliani broken-windowed into obscurity with brutal efficiency.

For much of the 1990s, the Mets seemed to have no entryway into this new world. The man who thought otherwise, who believed a path could be found and that he could chart it, was Fred Wilpon. The press conference during which Wilpon “fired” Vince Coleman was more than a wake-up call to his players. It was a wake-up call to himself and to the world. It was the first public sign that, for good or ill, he would run the Mets’ show from this point forward.

Both Fred Wilpon and Nelson Doubleday were dedicated baseball fans devastated when the Giants and Dodgers moved west in 1958, but the two men had little else in common. Doubleday inherited a fortune from his family’s namesake publishing house. His approach to team ownership fit his background: assemble a solid portfolio and let your assets do the work. He bore a vague resemblance to former New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller, his distinguished silver hair and his respectable yachtsman’s tan betraying his background as a well-off man of leisure. Meanwhile, Fred Wilpon grew up as the son of a funeral director in Bensonhurst and mined his own fortune in the cutthroat world of real estate. He had not inherited his fortune, but hustled and scrapped his way to it, as Doubleday would soon find out.

When Wilpon bought into the Mets in 1980, he owned a mere 5 percent of the team, but he had his eyes on much more and quickly found the means to get it. In 1986, Nelson Doubleday sold Doubleday Publishing to the German conglomerate Bertelsmann but intended to retain control of the Mets. (On paper, his stake in the team was owned by the publishing company, not Doubleday himself.) He foresaw no barriers to doing so until he encountered a contractual complication: Wilpon possessed first right of refusal in any sale of the team and could make the resale process difficult and protracted for all parties involved. Though Doubleday had no idea when or how Wilpon had done this, he was forced to come to a settlement whereby the two of them would purchase the Mets from Bertelsmann for $81 million. They would be equal partners, and barely on speaking terms, from that day forward.

Around the same time as his shape-up-or-ship-out presser in 1993, Wilpon felt confident enough to reveal his grand vision for the Mets to Sports Illustrated. He wanted to send Shea Stadium’s employees to the same rigorous hospitality training as Disney World employees, the gold standard of customer service. He dreamed of replacing the Mets’ ballpark with a sprawling entertainment complex topped by a gleaming retractable dome, surrounded by pavilions housing a permanent world’s fair resembling the one that Robert Moses placed alongside Shea Stadium in Flushing Meadows Park back in 1964. To New Yorkers of a certain age, that world’s fair still evoked New York’s prelapsarian glory, its exhibits of the glories of space age technology and better living through science a symbol of a simpler, more hopeful age. In the late 1990s such notions seemed quaint to many, but not to Fred Wilpon.

Wilpon was sure the Yankees had not taken the city for good. His new facility plans were an expression of this faith, a belief that harkened back to the long-gone days of that world’s fair, when the world came to Flushing, when Queens was a place where you could dream of the future, when Shea was a crown jewel, when the Mets were kings.

After Bobby Valentine’s brief sojourn to the Far East in 1995, a small miracle was required for him to return to the major leagues. That miracle occurred when another manager was somehow judged more controversial than him.

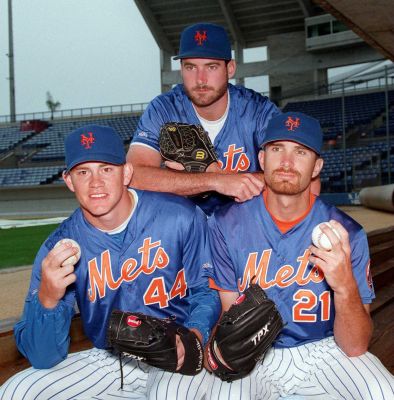

While Valentine was toiling away in Japan, the attention-starved Mets promoted a trio of hard-throwing pitchers from their farm system and dubbed them Generation K, a play on the Generation X label that was already several years out of style by that point. The belly laughs induced by the phrase “Generation K” notwithstanding, all three hurlers were ranked among the best prospects in baseball and rightly stirred excitement for the future from Mets fans desperate for hope. All three had also shouldered tremendous workloads as minor leaguers. This gave the Mets no cause for alarm because it wouldn’t have alarmed any front office in the mid-1990s, when pitch counts were not yet tallied like the ticks of a time bomb. The Mets were far from the only team that would lose promising young arms to the surgeon’s knife. The Mets were, however, the only team proclaiming they possessed three aces and daring to call them (snicker) Generation K. Each member of the ill-fated trio—Bill Pulsipher, Paul Wilson, and Jason Isringhausen—pitched indifferently after their promotions when not lost to the disabled list (which happened often). Generation K’s failure to be phenoms right out of the gate proved a PR disaster, one that was exacerbated by manager Dallas Green calling out his team for rushing the young pitchers to the bigs. “These guys don’t really belong in the big leagues,” he griped in August of 1996. “It’s that simple. It sounds very harsh and very negative. But what have they done to get here?”

With the Mets muddling through another disappointing year, Green’s ill-advised criticism of Generation K (accurate though it may have been) led to his dismissal with thirty-one games left in the 1996 season and the promotion of Bobby Valentine to the big league job. Upon receiving the news, Valentine rented a car to make the long drive from Pawtucket, Rhode Island, where the triple-A team was playing at the time, to Queens. Once he got within range of New York’s sports talk radio station, WFAN, Valentine tuned in to see if word of his hiring had leaked out yet.

It had. Valentine was treated to an endless string of callers moaning about the new Mets manager. Valentine’s an idiot. How can the Mets do this? Bad decision . . . Somehow he endured two hours of such masochism before shutting the radio off.

Fans weren’t the only ones skeptical of the choice. Dallas Green was seen as the tobacco-juice-spattered old-school skipper, while Bobby Valentine was considered his spiritual opposite: worldly, sophistic, cerebral. His stint with the Rangers was regarded as undistinguished at best, his time in Japan a demerit for its utter foreignness. Traditional sportswriters couldn’t understand why he asked his pitchers to watch video of opposing hitters during batting practice rather than shag flies. They understood even less when Valentine admitted he learned Japanese using a computer program and developed a liking for the internet because of it. In the mid-1990s, when cyberspace was the exclusive province of nerds, what kind of manager thought he could learn anything about baseball from the internet?

In 1997, Valentine dismissed some of these doubts by captaining the Mets to their first winning record in seven years, despite having few stars on his roster. The two exceptions were switch-hitting slugger Todd Hundley, owner of the single-season home run record for his franchise and for all major league catchers (41 in 1996), and John Olerud, a surprise off-season pickup who would anchor the Mets’ lineup and rejuvenate their infield for three seasons.

Though he’d won two championships and a batting title in Toronto, John Olerud’s batting average took enough of a dip after the 1993 season that the Blue Jays feared his best days were behind him. He was a quiet man, given the ironic nickname Gabby because he rarely spoke at all, the type of athlete New York is supposed to devour whole. The fact that he wore a batting helmet in the field—a precaution he adopted after an aneurysm nearly killed him as a minor leaguer—struck some as a sign of deeper fragility. His manager in Toronto, Cito Gaston, couldn’t imagine Olerud would cotton to Gotham, and vice versa. “I wouldn’t be surprised if he walks away from baseball at the end of the season,” Gaston predicted after Olerud was traded to Gotham.

Defying this pessimism, Olerud found that New York fit him like a glove. More intellectually inclined than the average ballplayer, he took advantage of all the culture New York had to offer. He eschewed the suburbs of Long Island or Connecticut for an apartment in Manhattan and even took the 7 train to the ballpark for many home games. His cultural yearnings and proletarian transportation choices would have meant little if he hadn’t performed, however, and in 1997 Olerud knocked in 102 runs, belted 22 homers, and logged an on-base percentage of .400. He was rewarded with a two-year contract extension the following winter.

As surprising as his resurgence at the plate was, his performance on the infield was even more shocking. In Toronto, Olerud’s lack of speed made it difficult for him to handle the balls that zipped across the SkyDome’s artificial turf, but on the slower natural surface of Shea Stadium, he became a wizard with the glove and a weapon at first, charging in on bunts and cutting down lead runners with a strong arm he’d never had a chance to display on Toronto’s unforgiving carpet.

Olerud’s example would prove the catalyst for one of the team’s biggest assets in the coming years. Taking his cue from the new infielder, third baseman Edgardo Alfonzo began to play his position with similar aggressiveness. Meanwhile, shortstop Rey Ordóñez emerged as one of the most dazzling players to ever man his position. The Mets’ starting pitchers at the time were mostly control artists who logged far more grounders than strikeouts. Fielders like Olerud, Alfonzo, and Ordóñez compensated for this lack of firepower by making sure those grounders became outs. Thanks to Olerud, the Mets had improved their pitching without acquiring a single new pitcher.

When a ball did manage to sneak past the infield, Olerud made the batter’s time on the basepaths uncomfortable. Rather than play on the bag or behind the runner, Olerud stood in front of him, screening him from the action, stalking his every move. Opposing teams believed Valentine asked Olerud to play first base this way for the same reason they assumed he did everything else—to be a jerk—but when pressed, Valentine said he was simply letting Olerud be himself. New York and Bobby Valentine found a way for Gabby to speak loudly.

On June 16, 1997, the advent of interleague play brought with it the first regular-season Subway Series game. In front of a sellout Yankee Stadium crowd, the Mets shocked their hosts with a 6–0 victory. Starting pitcher Dave Mlicki—a man even most Mets fans couldn’t pick out of a lineup—went the distance, scattering nine hits and striking out eight Yankees, six of them looking (including Derek Jeter), to end the game.

By the ninth inning, with most Yankees fans having long since left, the House That Ruth Built rang with foreign chants of “Let’s go Mets!” Stung by this humiliation, the Yankees rebounded to win the last two games of the series. The final contest was particularly contentious, as the Mets rallied late from a 2–0 deficit and scored the tying run when David Cone (by that point a Yankee, and regarded as an elder statesman by local press who never mentioned his earlier indiscretions) balked home a runner in the top of the eighth. Yankee manager Joe Torre later complained, “Bobby tried to plant the seed early,” claiming that Valentine pointed out an odd hitch in Cone’s delivery to the home plate umpire. Mr. Baseball countered that he was doing a favor for the less perceptive by pointing out a balk move when he saw one. Valentine’s eagle eye merely prolonged the game for the Mets, however, as the Yankees prevailed in walk-off fashion in the bottom of the tenth.

The first Subway Series in 1997 established the pattern that would continue for Met-Yankee summit meetings in the following years. The Mets would receive kudos for giving the Yankees a good fight if they lost, while reserving the right to treat each victory like a mini World Series if they won. “It was a great three days, wasn’t it?” said Edgardo Alfonzo at the conclusion of the inaugural series. His team had lost two of three games in the Bronx, yet he could proclaim the series “great” with no fear of drawing criticism.

The Yankees, expected to win the real World Series, would treat the affair with a mixture of contempt and dread. Playing the Mets in contrived circumstances offered them little to win and everything to lose. David Cone told reporters that dropping two of three to the Mets would have sent him scrambling for a cyanide tablet. Derek Jeter said such an outcome would have forced him to move to New Jersey. (He would repeat variations on this odd “threat” often in the years to come, apparently believing there were no fans to hassle him in the Garden State.) After Tino Martinez sealed a Yankee win in the first series finale with a walk-off RBI single, he said it lifted a ton of bricks from his back. Former Mets who had migrated across town, like Cone and Doc Gooden, were constantly polled about the differences between the squads and chafed at the constant questioning. One reporter noted that upon being called up to the Yankees on the eve of the first Subway Series, Wally Whitehurst (another ex-Met) asked his old teammate Gooden when pizza would be delivered to the clubhouse. He’d asked this in jest, but Doc answered it with deathly seriousness. “We don’t do that stuff here, Wally,” he warned, looking over his shoulder to make sure no team officials had heard the impudence. “This ain’t the Mets.”

There was no better demonstration of the tension between the two camps than the scene at Shea Stadium on April 15, 1998. Two days earlier, a five-hundred-pound support beam collapsed at Yankee Stadium, shutting down the House That Ruth Built until city inspectors could ensure the facility’s safety. The Mets were scheduled to play a game that evening but invited the Yankees to use Shea Stadium for the afternoon to complete their series against the Angels.

It was a neighborly gesture that satisfied no one. Mets players fretted that welcoming the Yankees into their stadium would have the same effect as inviting vampires into one’s home. Yankee players called the temporary relocation a “distraction” and dressed in the Bronx rather than dare use the facilities at Shea. Yankees fans who descended on Flushing that afternoon compared the temporary digs unfavorably to the self-proclaimed Cathedral of Baseball (“NOT BAD FOR A MINOR LEAGUE PARK” read one wag’s sign). Mets partisans who arrived that evening said the place would need fumigation after being invaded by those fans and bristled over team ownership accommodating their most hated rival.

The first Subway Series had been marked by full-blown fistfights in the Yankee Stadium stands. Players contemplated popping cyanide tablets if they lost. One fan base compared the arrival of the other team’s fans in their stadium to an infestation of pests. A local sports radio personality dismissed the idea that New Yorkers could root for both teams by proclaiming, with the fervor of a Baptist preacher, “You can’t be for God and the Devil!”

The media made note of all this animosity, but only to dismiss it. In their estimation, the Subway Series was a unifying civic event that uplifted the entire city. Everyone said so, from the mayor on down. “It’s wonderful for the city,” Rudy Giuliani said of the event. Every outlet of officialdom adopted this line as their own, ignoring Giuliani’s own recollection of a youth when Dodgers and Giants fans couldn’t be in the same room together without fighting. Brawls in the stands were labeled “skirmishes.” Hate-filled volleys from one team’s fans toward another’s were placed under the umbrella of playful exuberance.

The press ran with the mayor’s contention and took it one step further. Now that New York had returned to its former glory, the only thing it was missing was a real Subway Series. If midsummer games between the Mets and Yankees were a civic boon, then an October showdown would be even more of one. Wouldn’t that be great for the city? the scribes would coo, blind to all the evidence they gathered that said otherwise. Or as if such a contest would settle a question presented by the teams’ continued coexistence: If the city could only be owned by one team, which team would lay claim?

The 1997 season was an eventful one for the Mets, both for the advent of the Subway Series and for the ascension of a long-promised wunderkind to the head of the front office food chain. In July, thirty-four-year-old Steve Phillips was given the general manager’s chair, making him baseball’s second-youngest top executive. (Detroit’s Randy Smith edged him out by a month.)

After a brief minor league career in the Mets organization, Phillips joined the executive set when Joe McIlvaine offered him his first front office job in January of 1990. From the start, it was clear the Mets eyed Phillips as their executive of the future. For years, his quotes could be found throughout the city’s back pages with a frequency belying his obscure (if important) position as director of minor league operations. After the 1995 season, when Phillips was named assistant general manager, his name was being whispered as the imminent replacement for McIlvaine, whose relationship with team ownership had deteriorated beyond repair. McIlvaine’s preference for team building via the slow and unglamorous player development process had already produced one major flameout in Generation K before it was undone completely by the failure of Ryan Jaroncyk, a Mets first-round draft pick who quit the game altogether early in the 1997 season while confessing that he’d always thought baseball was boring. There were many factors prompting Jaroncyk’s premature retirement, most so personal they would have escaped any executive’s notice, but Mets ownership drew one simple conclusion from his example: Joe McIlvaine’s way didn’t work. The newest iteration of the Mets would therefore not construct itself through sober accumulation of young talent, but through flashy quick fixes. Six weeks after the Ryan Jaroncyk debacle came to light, Joe McIlvaine was “reassigned” in the Mets’ front office and replaced with his protégé Phillips. Upon introducing his new general manager to the press, Fred Wilpon—in a line destined to be repeated back at him for years to come—insisted Steve Phillips possessed executive “skills sets” that his predecessor lacked.

For much of the twentieth century, a general manager’s job was closer to that of chummy middle managers in the Gray Flannel Suit era, deals settled over three-martini lunches by execs who rarely worked beyond 5:00 p.m. By the late 1990s, however, the position was fully corporatized and held the expectation of being perpetually on the clock and under the microscope. Phillips embraced this view and marveled over reminiscences of times early in his executive career when he witnessed Frank Cashen and Al Harazin sitting in their Shea Stadium suite reading, discussing not trades or free agents but current events. Imagine, he would recount with a shake of his head, a general manager who had time in his daily schedule to contemplate a world outside of baseball.

Bobby Valentine and Steve Phillips were like two notes a semitone apart, too similar to ever form pleasant harmony. Like Valentine, Phillips relished the spotlight. Like Valentine, Phillips had a high opinion of his own baseball knowledge. (Phillips’s insistence on visiting his manager’s office before and after almost every game to discuss strategy would prove a pain point.) Like Valentine, Phillips possessed a myriad of foibles that tended to land him in trouble (though Phillips’s foibles were of a different stripe; more on that later).

As for their differences, Phillips possessed a more selective filter between his brain and mouth. (“Sometimes I wish I had the ‘no comment’ in me,” Valentine confessed in grudging admiration.) Whereas Valentine’s relationship with reporters was strained at best, Phillips played New York’s sports press corps like a fiddle, providing quotes, access, and background to all comers. His sartorial sense and articulation allowed him to adopt the part of the young go-getter: impeccably dressed, perfect coif of sandy hair, accented by wire-rim glasses whenever it was time to look serious. He possessed the air of the spokesman an embattled corporation would send before the cameras to assure the public that, despite all the nasty rumors, their product was perfectly safe.

Joe McIlvaine had brought Bobby Valentine back into the Mets organization for his ability to teach the game to young players, calling him “one of the best teachers of baseball there is.” Such skills were not treasured by a front office headed by Steve Phillips, however. Phillips referred to the overachieving Mets of 1997 as “a good little team with good little players.” If that reads like condescension, he surely intended it as such. When McIlvaine was demoted, then departed for the Minnesota Twins—a small-market team whose only hope at competing was to develop good little players—Valentine was left behind to wonder how he fit into the Mets’ new equation.

Phillips began his first off-season by taking advantage of the Marlins, as many teams did that winter. Florida loaded up on high-priced superstars in 1997 to fuel a stunning World Series victory, then dismantled themselves before the victory parade confetti had settled. Phillips got in on the fire sale by shipping three minor leaguers to the Marlins in exchange for left-handed pitcher Al Leiter.

A New Jersey native, Leiter enjoyed up-and-down years with the Yankees and Blue Jays before finding his form with Florida, where he played a key role in the Marlins’ championship. Though a veteran, he more resembled a Little Leaguer who took the game a bit too seriously. He was prone to both losing his focus and criticizing himself to worrisome extremes. He had idiosyncratic on-field habits, such as jumping in the air and clicking his heels to clear mud from his spikes. More troubling was Leiter’s propensity to argue with his managers to remain on the mound far beyond the point most pitchers would, which sometimes saved a call to the bullpen but just as often led to a blown lead.

These shortcomings could be tolerated because Leiter was a very good left-handed starter who could often fight his way to greatness. When he joined the Mets’ starting rotation, he became its best member by a wide margin. He was thrilled to join the team he grew up rooting for as a kid from Toms River, even if he would have to play for a manager who once tried to psych him out from the opposing dugout by screaming, “You’ll never make it out of the fourth inning!” As big as the Leiter trade was, though, Steve Phillips’s biggest deal was yet to come.

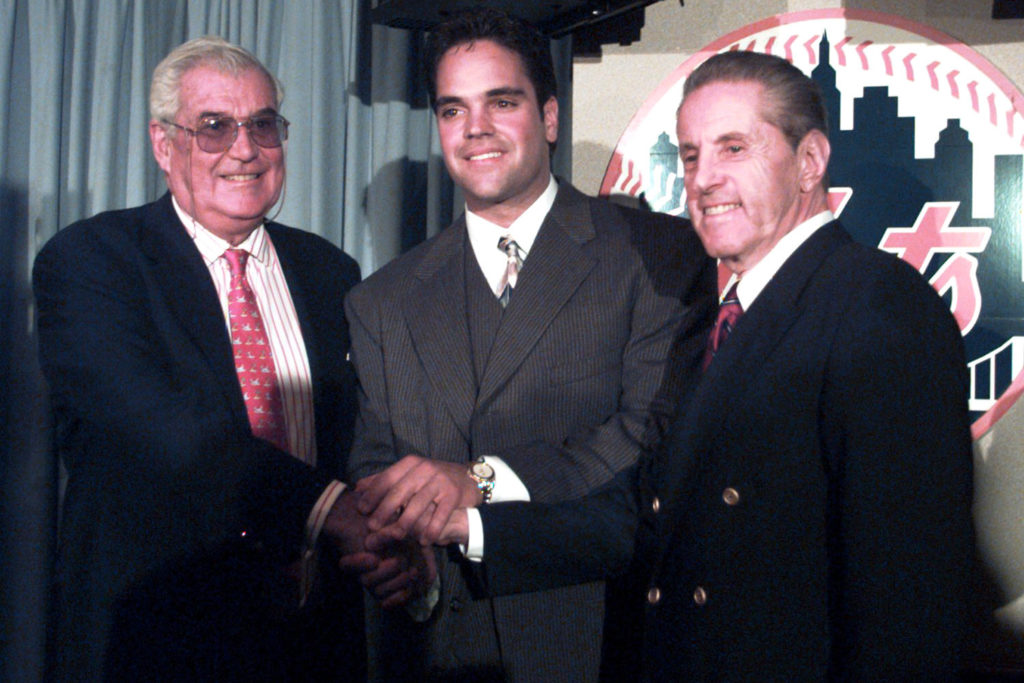

Out in Los Angeles, free agency loomed for Mike Piazza, who had already established himself as one of the best-hitting catchers in baseball history. His desire to remain with the Dodgers began to sour when the team rejected his agent’s contract terms, then curdled even more after the Los Angeles Times conducted an interview with Brett Butler, an ex-teammate, who painted the catcher as “a moody, self-centered ’90s player” and insisted “you can’t build around Piazza because he’s not a leader.” It was a not-too-subtle hint that the team believed it could get by just fine without him, and Piazza chose to take the Dodgers at their word. As the 1998 season began, divorce proceedings progressed quickly, and a trade was executed on May 14 that shipped Piazza off to Florida. The payroll-hemorrhaging Marlins were a mere layover for the catcher. The only question was where he would fly to next.

On the back pages and sports talk radio airwaves in New York, the chatter screamed for him to land with the Mets as a replacement for Todd Hundley, who would miss much of 1998 recovering from Tommy John surgery. For days, WFAN’s drive-time duo Mike and the Mad Dog fielded almost nothing but frantic calls from Mets fans demanding that the team make a deal for Piazza. Though team ownership was reluctant to replace Todd Hundley, one of their few genuine stars, Fred Wilpon became convinced that this was a deal that had to be made after hearing the fervor of the fans screaming for action on the radio.

Eight days after Piazza left LA, Steve Phillips made the trade that brought him to New York and immediately made him the best hitter to ever wear a Mets uniform. He started slowly in New York before stepping on the gas, hitting .351 in the second half of the season and .378 in September. As soon as he took off, so did the rest of the Mets. John Olerud flirted with a batting title, Edgardo Alfonzo complemented his slick fielding at third base with strong production at the plate, Rey Ordóñez acted as a human vacuum at shortstop, and Al Leiter was as good as advertised. On September 20, the Mets’ win-loss record stood at 88–69. They held a half-game lead in the wild card standings, just ahead of the surging Cubs and Giants, with five games left to play.

And then, as if someone flipped a switch, everything stopped working all at once.

In their last two home games of the year, the Mets faced a middling Montréal Expos team that had inexplicably given them fits all season. The Expos lost ninety-seven games in 1998, yet won eight of twelve games against the Mets, and none were more damaging than this last pair. On the evening of September 22, Mets starter Armando Reynoso—perturbed by unseasonably cool temperatures that “seemed to signal the onset of autumn,” in the ominous words of the Daily News—allowed a lead to evaporate as New York went down in defeat, 5–3. The next night, the Mets were shut out by rookie hurler Carl Pavano.

To finish out the year, the Mets traveled to Atlanta to play three games against the Braves. There was no rivalry between the two teams at that time, unless an insect can be said to have a rivalry with a bug zapper. While Atlanta captured division titles through the 1990s, New York offered no threat to their dominance whatsoever. When the Mets arrived at Turner Field on September 25, the Braves had clinched yet another division crown almost two weeks prior and had won 103 games. The visiting team had everything to play for. The home nine had no concerns but the upcoming playoffs.

And yet, the Braves were the ones who played like a team on a mission, while the Mets played like a team just learning the game. In the first Atlanta contest, as the Mets trailed by two runs in the top of the eighth inning, Bobby Valentine used speedy September call-up Jay Payton as a pinch runner, hoping he could jet home from first on an extra-base hit and score the tying run. The move backfired when Payton attempted to advance to third on a two-out single and challenged the powerful arm of Atlanta center fielder Andruw Jones. The rookie was gunned down by a good five feet, having committed the two cardinal baseball sins of making the last out of the inning at third and doing so while Mike Piazza stood on deck. The end result was a 6–5 heartbreaker of a defeat. The Mets would come no closer to winning for the rest of the season.

In the second game in Atlanta, Al Leiter held off the Braves for five innings but faltered in the sixth, ceding more than enough runs to ensure defeat at the hands of Atlanta ace Tom Glavine. For the final scheduled game, Bobby Valentine was forced to send the shaky Armando Reynoso to the mound because his preferred starter, Hideo Nomo, had pitched poorly since a midseason trade to New York and begged off the assignment, citing pride, despite excellent career numbers against Atlanta. Reynoso was shelled for five runs before the end of the second inning and the Mets went on to lose yet again. Atlanta manager Bobby Cox seemed to relish the conquest when he compared sweeping Valentine to defeating Casey Stengel and John McGraw, a contention that had the ring of sarcasm to it. (Valentine chose to take this as a compliment.)

To pour extra salt on the Mets’ wounds, the Cubs and Giants finished the season in a tie for the wild card, necessitating a one-game playoff. If the Mets had won a single game of the five they dropped to close out the season, they would have found themselves in a three-way wild card tie. If they’d won two, they would have captured a playoff spot outright. Instead, they won a premature trip to the golf course.

The entire organization took the loss hard, but no one took it harder than Bobby Valentine. Normally impossible to shut up, the manager was at a loss for words. “I don’t know what happened,” Valentine told reporters. “If I knew, I would have done something about it. That’s my frustration about it. Everything I tried didn’t work.”

If Steve Phillips felt the same devastation, he did a better job of hiding it. “My hopes were grander than just getting to the playoffs,” he admitted after the Mets’ final, brutal loss. “But I’m also excited about putting a team together for 1999. And that’s what’s getting me through today.”

Steve Phillips was never a man for the long view. As he set about the business of assembling the next season’s roster, it is unlikely he gave much thought to one minute beyond 1999. And yet, almost despite himself, Phillips would assemble one of the most beloved teams in franchise history.