Introduction

What follows is the Introduction that will appear in Yells For Ourselves. It serves as a statement of purpose and summary of what the book hopes to achieve. Those who want an idea of what this book is all about should start here.

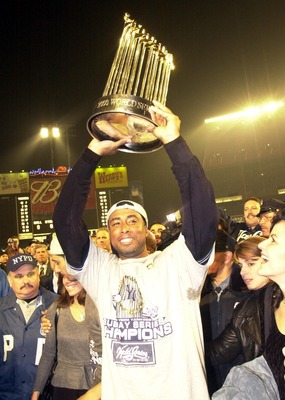

The last out of the 2000 World Series came off the bat of Mike Piazza. With two out in the bottom of the ninth and a runner on second, he clubbed a Mariano Rivera pitch to straight away center field, the deepest part of a deep ballpark. For a moment, the Shea Stadium crowd could dream of a game-tying home run, of playing another day. Like much of what the Mets had done in the series—in the last few seasons, really—they came up just short. Bernie Williams tracked the ball to the warning track, mere feet from the fence. It settled in his glove, and the Yankees had captured their third straight championship.

The victorious team stormed the field to celebrate, while the vanquished one fixed them with thousand-mile stares. The winners were technically the visitors, even if they were playing within the confines of the city it was often said they “owned.” There were no fireworks, no scoreboard pyrotechnics, no blasting of “We Are the Champions” or “New York, New York.” The huge Diamond Vision screen beyond the outfield fence gave no indication a title had just been won; it merely advised fans to drive home safely, nothing more. Despite the presence of many Yankee fans in the stadium, the cheering was scattered and intermittent, trickles of gray amid a sea of blue and orange. The only pronounced sounds were the Yankees’ joyous howls and the Shea Stadium organ, churning out a plaintive rendition of Thelonious Monk’s “’Round Midnight.” For a scene of such celebration to receive a muted reaction like this, accompanied by nothing more than a melancholy tune tapped out on the organ, was unsettling, almost eerie.

The victorious team stormed the field to celebrate, while the vanquished one fixed them with thousand-mile stares. The winners were technically the visitors, even if they were playing within the confines of the city it was often said they “owned.” There were no fireworks, no scoreboard pyrotechnics, no blasting of “We Are the Champions” or “New York, New York.” The huge Diamond Vision screen beyond the outfield fence gave no indication a title had just been won; it merely advised fans to drive home safely, nothing more. Despite the presence of many Yankee fans in the stadium, the cheering was scattered and intermittent, trickles of gray amid a sea of blue and orange. The only pronounced sounds were the Yankees’ joyous howls and the Shea Stadium organ, churning out a plaintive rendition of Thelonious Monk’s “’Round Midnight.” For a scene of such celebration to receive a muted reaction like this, accompanied by nothing more than a melancholy tune tapped out on the organ, was unsettling, almost eerie.

At the time, it seemed the organist made an oppressively literal choice, since the final out came at 12am. The passing of time has made it more subtly appropriate. When the Mets lost the 2000 World Series, the clock struck midnight for them in many senses. Their dreams of overtaking the Yankees in the hearts and minds of New York sports fans–no matter how unlikely such an outcome may have been–were over. Any desire on the part of the media to convey a nuanced portrait of either team during this era had also ended.

So too had ended any serious attempt on the Mets’ part to build within or plan for the long term. Ironically, though the Mets’ approach to winning in a World Series in 2000 was unsuccessful, they would follow its model for the next decade plus, continuing to spend and trade with little thought for the future, going about their business as if This Season and only This Season mattered. This was tragic for a multitude of reasons, but above all because such a mentality caused the Mets, as an organization, to turn its back on its own history and even its notions of self. What ownership thought fans wanted was a championship, which was true to an extent. But in truth, what fans really wanted more than anything else was another 1999.

Among fans of a certain age, it is an article of faith that the 1999 Mets were a superior team to the pennant-winning squad that followed. In my own anecdotal experience, I’ve found it nearly impossible to encounter a Mets fan who’d argue otherwise. In 2009, I wrote a series of day-by-day retrospectives on the 1999 Mets for my blog, Scratchbomb.com, and received dozens of emails from fans who loved the 1999 team. More often than not, these emails would offer the opinion that the 1999 team was better than the 2000 team. No prompting on my part was necessary to elicit this opinion. At first, I didn’t question this notion because it reaffirmed my own biases; I also preferred the 1999 team to the 2000 one, though I couldn’t quite articulate my reasons for feeling this way. The 1999 Mets were a special team, possessing all the qualities of the romantically doomed. After years of adolescent sports agnosticism, the 1999 Mets made me feel like cheering for a sports team was a worthwhile use of my time. Memories of the 2000 team, on the other hand, were tinged with more than a little pain.

Eventually, I decided that the 2000 team would need a closer examination to see if these reflexive prejudices against them had any merit. After researching the 2000 season for a series at Amazin’ Avenue.com, I came to the conclusion that this team was better than fans’ memories gave it credit for. However, I also came to the conclusion that the 2000 team’s objective merits ultimately don’t matter, because it lacked certain qualities that the 1999 team had in abundance. An outsider might find it puzzling that the 2000 Mets, which made it all the way to the World Series, are less beloved than the 1999 team, which fell short of that mark. Only when placed in the context of the Mets’ history and the ethos of its fanbase does this assessment makes perfect sense. The 1999 team fulfilled many aspects of what a Mets fan expects of his team, and expressing a preference for this team is, in itself, an expression unique to Mets fans.

To understand why this is, we first have to ask ourselves the question: What is the point of a sport? An athlete would tell you his or her goal is to capture a ring, but the vast majority of people who engage in a sport don’t play it professionally. Most of us simply observe, and for the spectators, the point of a sport is not to have a championship won on our behalf, even though we all dream of our favorite team doing so. As much importance as we ascribe to it, as much “agony” as we think it puts us through, a sport is primarily entertainment for the observer. There are a myriad of ways in which sports can entertain us that don’t necessarily end with a champagne-soaked locker room.

In other entertainment fields, we accept that something can be enjoyed even if it isn’t an unqualified success. We don’t think, for instance, that the only films we can treasure are the ones that win the Oscar for Best Picture. Of course, when it comes to an artistic endeavor such as filmmaking, the array of means we will accept as entertainment is far wider. In a sports context, watching our favorite team win tends to be more entertaining than watching them lose. But winning is not the sum total of what fans want. It’s of primary importance to fans that these wins are achieved in the way we expect from our team, and that the players on those teams—even the best ones—perform in the way we expect as well.